A review of The Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-machine Interface and thoughts on fractured identities, which are really thoughts on whether or not the soul can be made digital.

Review: The Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-machine Interface, Masamune Shirow, 2001.

The long-awaited sequel to The Ghost in the Shell came in 2001, and it was shocking. Even though today it is common to read GITS 1.5 (Human-error processor) first, I've decided to stick with the Western publishing order, in large part to maintain that shocking effect.

At the end of the first volume, Major Motoko Kusanagi has merged with an AI (just like in the 1995 film adaptation), and the sequel finds her some years after this event.

The idea of a post-human or digital-human or pseudo-demi-digital-gods is not new to cyberpunk. What is new, and what nobody before or since has done, is give an interpretation of the idea that is this dizzying and disorientating.

Man-machine Interface is a work that elides traditional narrative and setting concepts. Instead of a neat divide between setting and protagonist —– the protagonist is the setting. We are always peering through the eyes of Motoko Aramaki, as she exists in both physical reality and cyberspace, jumping from body to body and location to location. Crucially, Motoko almost never travells anywhere; she holds brain-to-brain conferences, she rides a motorcycle as one body, while at the same time deep in a virtual hacking maze trap, while in the same body but a different “frame” of consciousness.

Visually, Shirow further adds to this effect. The panel and model overlap, which is a hallmark of manga, is here extremely aggressive and taken to almost comical extremes. Further, unlike the first volume of the manga, which had a relatively restrained, traditional visual style, Shirow here uses garish CGI, bright colours, and gratuitous nudity.

For a work that deals in fractured identities, non-local consciousnesses, and posthumanism, it works. Shirow resists trying to make Man-machine Interface legible (roughly 50 per cent of the dialogue is impenetrable technobabble) and digestible. There are no explanations or justifications for the weird and the uncanny (Shirow is a fan of adding marginalia to his work, but here they only end up adding even more confusion), and no clear frame of reference for how all the different events we witness connect chronologically.

Even the introduction of explicitly spiritual Shinto elements in the prologue and epilogue, which at first glance might just serve to provide this unifying frame for the experience, ends up being ambiguous and most likely shouldn't be taken literally.

Combined, all of this creates a strong Verfremdungseffekt, distancing us wholly from the protagonist and her narrative. The technobabble thus becomes elevated —– we don't know what Motoko is talking about, but she does.

Motoko is not a relatable character, and the events are abstract, yet none of this matters because this is Shirow in his element. It's one provocative idea after the next, one garrish panel after another, creating an almost hypnotic effect of the uncanny.

The Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-machine Interface is ugly, fetishistic, and it doesn't make sense. Grade: 10/10

Entrement: Have we ever been postmodern?

The uncanny is really the point. Why have an expectation that a wholly new life form will make itself legible to you? And how will we, as we live with this and work AI into our own lives, become different? Will we be legible to ourselves even?

There's something in this idea of fractured identity that is both relevant to our present moment and echoes the writings of early postmodernists. This fluidity that is now almost native to us, one identity for Instagram, another for LinkedIn, at the face of it —– it looks liberating, but is it? As identity splits, surely it becomes depleted somehow, and all the fragments are an imperfect image of the whole.

Or is identity infinitely divisible and mutable like the postmodernists teach? This is what the current Silicon Valley proponents of AI and transhumanism believe.

But, I'd say, as much as we are obsessed with identities these days, the true question and true frontier is, and has always been, the soul.

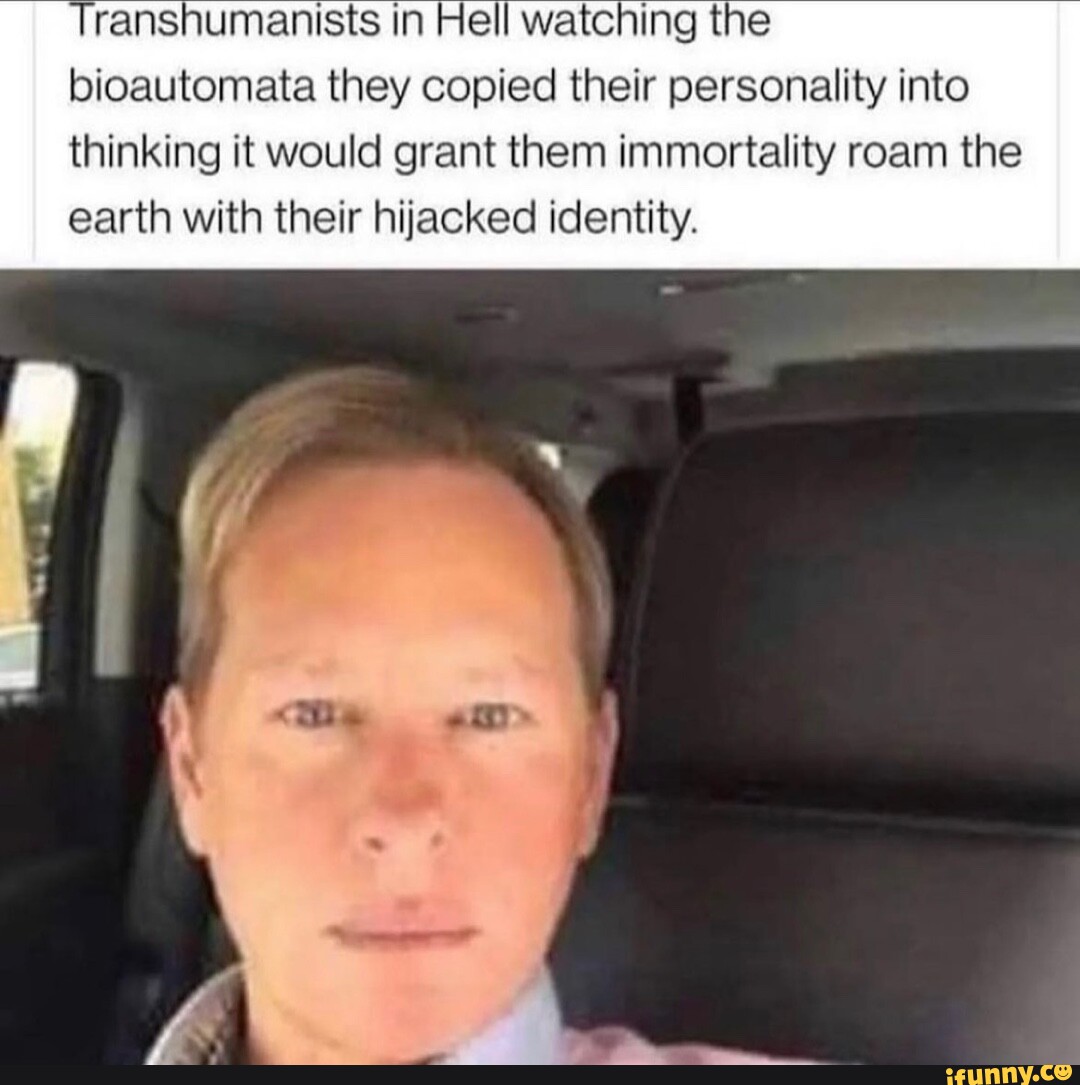

Consider the image above as Meta patents an AI that can take over your account when you die.

Dessert: The flavor of the Age to Come.

There's a devilish side to AI and transhumanism. Many stories across time and space warn us of the dangers of raising the dead. Or trying never to become dead.

The first volume of The Ghost in the Shell ends on a somewhat hopeful note. The merging of human and AI is seen as a new frontier full of possibilities and wonder. The sequel is not as cheery, and not as cheery as today's proponents of AI and transhumanism are.

It's hard not to see a parallel with how our society went from the digital utopianism of the late 90s and early 00s to this enshittification-aware, social-media-fatigued state, qualityslop-deluged where many of us just kind of wish the Internet would cease to exist.

There is a belief among some, and this is a common trope in cyberpunk and now on Twitter, that a human's Self (Soul, Ghost, Psyche, etc.) is really nothing more than a heap of data. And data can be stored and copied, and transferred, so all that needs to be done is to somehow convert analog brain signals into digital code, and Bob's your uncle.

We should remember a very interesting episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation, in which Data, faced with being disassembled and his memory stored elsewhere, discusses the flavor of memories. Disembodying memory takes the flavor away.

In the Christian tradition, disembodying the soul, which is the event of death, is meant to be the beginning of the eventual transition into the Age to Come, and the faithful are assured that no flavor will be lost in this. Actually, it's hard to imagine that if eternal communion with God does have a flavor, it wouldn't taste good.

We can't be so sure exactly what things will taste like if the Elon Musks and Alex Karps of the world have their way and we begin merging our brains with direct digital input.

But, narrative convention and the fact that God is supposed to have a sense of humor, compel us to believe that once “turning analog consciousness into digital data” does become “possible,” what will actually take place is an LLM-like simulation of a human soul.

The digital eschaton won't free us; it'll just kill us.

But our digital copies will keep posting memes.