What is qualityslop: an introduction to the slop world

This is an exciting time for the word “slop.” Slop is Merriam-Webster's word of the year, coworker slop is making the rounds in Slack inboxes, and goyslop, well, we don't talk about goyslop. Slop cropped up in the lexicon of the online far-right a little after the now semi-forgotten globohomo. That stands for both “global homogenization” and “global homosexuality,” by the way.

We’re all drowning in slop.

This is now a slop-based economy and culture. The slop-based economy works as such: the intersection of cheap labor and high technology enables mass production of things that are just good enough but are nothing special. If you’re a tech person, you know this as enshittification. If you’re in the humanities, you know it as kitsch. But neither of these can capture exactly what’s going on. Enshittification presumes that at some point, all the corporations truly cared about quality and customer satisfaction, which is a childish notion. Kitsch presupposes that there is such a thing as high and low culture, and most importantly, that anyone gives a fuck. Changes in technology and advances in automation and logistics have made it so that everything is produced in the same factory. This is true of material goods and immaterial products as well. It used to be easy to distinguish “quality” from “non-quality.” Quality was made by artisans and auteurs. Non-quality was mass-produced and disposable. This is no longer our world. We live in a world of disposable €2000 smartphones that go stale in 2 years and prestige TV shows with budgets in the hundreds of millions, based on popular video games, that everyone forgets in a year. Do you remember Castlevania, the animated TV show based on the eponymous Konami intellectual property? I didn’t think so, but a few years ago it was a rave. Just like McDonald’s fries, devour it now because in 15 minutes it’ll be cold and soggy.

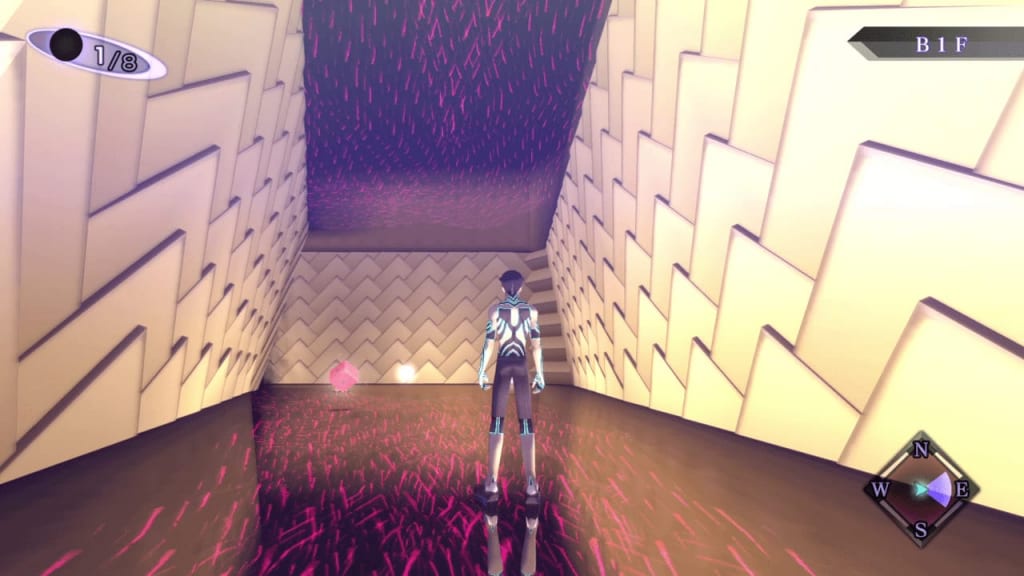

The primary feature of the slop-based economy is a loss of haecceity. For those who play video games, the explanation will be the easiest to understand. Once upon a time, each individual game felt like its own entity with its own controls, gameplay features, etc. Today, controls have been standardized as well as the camera perspective, so every game now looks like this: a (wo)man is walking through a corridor (or alley or cosmic void of nothingness, games love that one), followed by a low-placed camera framing the back and the ass in the lower left corner of the screen:

Which of the above is The Last of Us: Part II, and which one is Resident Evil Revelations 2? Actually, trick question. Those are screenshots from Alan Wake 2 and The Evil Within 2, respectively. An even easier to grasp example is how mobile phones went from a bunch of different designs to being just black slabs, but I want to stick with video games since they’re at that intersection of art and technology where all human creativity actually is. It’s easy to mistake superficial differences in aesthetic and plot for deep markers of individuality. There aren’t any. It’s all the same thing, over and over again. Some have called it the PlayStation first-party game syndrome, as all these games are serious, feature grizzled males or tough women, and deal with such important and topical issues like humanity, individuality, civilization, and the thin veneer of it all in particular. They love that thin veneer. Snoozefest. Just like the latest iPhones’ ever-thinning bezels, the differences are measured in millimeters. Now, while I say snoozefest, the critics and audiences disagree. All these games were very highly rated.

Bringing us finally to qualityslop. Qualityslop are the things you only like because they’re good. Qualityslop is a product, physical or art or whatever else, that has lost its haecceity and now only exists within the category of whatever is socially constructed as “quality” in the given moment. Several places serve as the cathedrals of quality for the modern world. High-volume prestige publications like The New York Times still serve this purpose, but they are retreating before the two titans of contemporary thought-shaping: Reddit and YouTube.

Redditors are known primarily for their love of “quality of life features.” Go to any thread about a well-known or even well-liked video game, old or new, and Redditors will be talking about how much they love the QOL features. Or alternatively, how much they wished the game included some more QOL features. Artistic vision, atmosphere, game design, and challenge be damned — I want to be able to save anywhere.

I want to quickly examine just what happens when you listen to Redditors completely (sorry, it’ll be another video game example). In 2021, Atlus published the long-awaited follow-up to their flagship JRPG franchise Shin Megami Tensei. A few years later, they followed it up with an expanded edition subtitled Vengeance. Both of these versions owe a great deal of inspiration and influence to the company’s 2003 game Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne. That one is considered by many (and me) to be one of the best, if not the best, Japanese role-playing games of all time. Nocturne has style, ambition, and it’s uncompromising. It is exceedingly difficult, relentlessly dark, and it is my personal belief that the team actually did commune with demons when they made it. Oh, the SMT series, as it is known affectionately, is all about being Pokémon but with demons. (Fun fact: it came out several years before it.) Nocturne is minimalist; it’s focused on telling a story of survival and transformation in a demon-infested Tokyo as the protagonist assumes the role of the “demi-fiend,” a cursed creature that is part human and part demonic. To sell this idea of body horror, a world gone topsy-turvy during a cosmic event known as “the Conception,” when an old world dies, and a new one is born, the game chooses to be difficult, to intentionally introduce friction and frustration. Things don’t often go as you’d like in Nocturne. Demon fusions, which are needed to create powerful allies to fight alongside, have opaque and unexplained rules. You can only save in predesignated locations, and you’ll often die before you can reach the next save point. In Vengeance, you can save anywhere, and this annihilates most of the challenge of the game. Demon fusions are simplified with QOL features that allow you to select the exact skills you want the new creation to have. Any tension the game tries to introduce, such as having to use consumable items to change elemental affinities for your main character (these govern weaknesses in battle and are key to the system in which players and enemies can gain extra turns by exploiting them), is undercut by giving the player what is in essence an opt-out, you can purchase those items cheaply at any in-game shop. This list goes on. And in a stunning reversal of video game design philosophy, the newer game is actually less legible than its 22-year-old predecessor. Observe:

In the name of QOL, the bottom image from the new game is busy and overloaded with information. All the readouts and portraits reinforce that you’re playing a video game, interacting with a system that, once you remove the superficial stuff, is not all that dissimilar from a ClickUp dashboard. It’s been said, ars est celare artem, and Vengeance fails at this. At no point during my time with it did I feel like I was fighting to survive in a horrendous demon-infested world. I was merely optimizing my party and my skills. Yes, you also do this in Nocturne, but that’s the thing. Nocturne managed to disguise the art, the ClickUp mechanical part of the equation, and tell a story and create an atmosphere.

I mention legibility, as another feature of a slop-based economy is the emergence of a particular kind of illiteracy. This illiteracy is best exemplified by the YouTube video analysis essay. It’s so bad that it’s a meme — a 7-hour video essay to explain a 90-minute movie. These videos typically don’t have much to say; they have one or two theses, but they stretch them ad nauseam. Part of it is the much-maligned YouTube algorithm, which simply likes longer videos because people engage with longer videos longer. It’s dialectical: as people who don’t really get it try to talk about it, they get long-winded, and as the technique of the medium enforces long-windedness, people lose things to say. Writing clarifies the mind and thoughts; talking in front of a microphone has almost the opposite effect. Nevertheless, film and TV show makers are not oblivious to what’s going on. If you want visibility in a crowded world of streamers, why not focus on adding as much “deep lore” as you can so that some nerd can dissect it for 10 hours? The engagement formula is clear.

When Merriam-Webster chose the word “slop” as the word of 2025, they were doing it primarily because of “AI slop.” I won’t waste your time examining AI slop; everyone knows it, everyone has seen it, nobody likes it, but they are afraid of it. An even more horrifying reality: AI slop is not the cause of anything. It is the result. We’ve actually entered the slop-based economy long before AI even appeared. The reason why AI can emulate human writing and human artwork, or at least certain kinds of it, is because these kinds of it have become dominant in the slop factory that now spans the entire world. Every video game with QOL features thrown in, every quick and dirty illustration on a graphics tablet, every book and movie that insists on a three-act monomyth structure, that’s what made art mechanical and repeatable. Removing friction, removing creative risk, is why more and more TV shows, games, and movies feel like best-of compilations of prior works instead of new things with their own soul and identity.

Speaking of best-of compilations of prior works that can’t hold a candle to the original, there’s Nosferatu 2024. In my short Letterboxd review, I said that a remake of a foundational 100-year-old horror movie needs more than fashion photography and a prosthetic cock for Bill Skarsgard. I would ammend this now, after a conversation with a friend, that fashion photography and prosthetic cocks are no replacement for der Grauen. To take a creative risk, like choosing to make a critical video game system opaque and hard to understand, or like in the famous The Twilight Zone episode Eye of the Beholder to shoot ¾ of it with the actors facing away the camera, is to stand firm in the face of horror. Embracing tension and a lack of clarity, not trying to remove it, is what does remove it after the hard work is done. Clarification or enlightenment is not an easy task, it takes courage and guts.

In this gutless environment, where things have been flattened into slop, it’s no wonder that everything is made of slop. Low-effort cash grabs, slop. Prestige TV shows, slop. In a world made of slop, slop is slop is slop. There are no more ways to differentiate. Quality is what we say quality is on social media.

Welcome to Slop World. May I take your order?